|

| Home |

| 1 Ancient Mesopotamia |

| 2 Ancient Egypt |

| Ancient Greece |

| 3 Ancient Rome |

| Judaism and Christianity |

| 4 Byzantine and Islamic Civilization |

| Indian Civilization |

| 5 Chinese civilization |

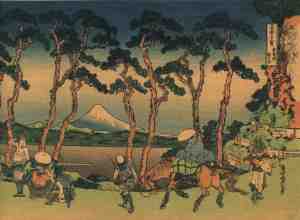

| Japanese civilization |

| Early American Civilization |

| 6 Early Ages, Romanesque, Gothic |

| Renaissance |

| 7 Baroque,18th,Romanticism, Realism |

| 8 Belle Epoque,Chinese & Japanese society |

| 9 Russian,Age of Anxiety,Africa, Latin Am. |

| 10 Age of Affluence, diversity |

|

|

|

|

|

CHINESE CIVILIZATION

Origins and Early History | The stone tools and fossils of Homo erectus found in N and central China are the earliest discovered protohuman

remains in NE Asia; some of the tools date to more than 1.3 million years ago. About 20,000 years ago, after the last glacial

period, modern humans appeared in the Ordos desert region. The subsequent culture shows marked similarity to that of the higher

civilizations of Mesopotamia, and some scholars argue a Western origin for Chinese civilization. However, since the 2d millennium

BC a unique and fairly uniform culture has spread over almost all of China. The substantial linguistic and ethnological diversity

of the south and the far west result from their having been infrequently under the control of central government.

China's history is traditionally viewed as a continuous development with certain repetitive tendencies, as described in the

following general pattern: The area under political control tends to expand from the eastern Huang He and Chang (Yangtze)

basins, the heart of Chinese culture, and then, under outside military pressure, to shrink back. Conquering barbarians from

the north and the west supplant native dynasties, take over Chinese culture, lose their vigor, and are expelled in a surge

of national feeling. Following a disordered and anarchic period a new dynasty may arise. Its predecessor, by engaging in excessive

warfare, tolerating corruption, and failing to keep up public works, has forfeited the right to rule—in the traditional

view, the dynasty has lost “the mandate of Heaven.” The administrators change, central authority is reestablished,

public works constructed, taxation modified and equalized, and land redistributed. After a prosperous period disintegration

reappears, inviting barbarian intervention or native revolt.

Although traditionally supposed to

have been preceded by the semilegendary Hsia dynasty, the Shang dynasty (c.1523-1027 BC) is the first in documented Chinese history

(see the table entitled Chinese Dynasties ). During the succeeding, often turbulent, Chou dynasty (c.1027-256 BC), Confucius , Lao Tzu , and Mencius lived, and the literature that until recently formed the basis of Chinese

education was written. The use of iron was the main material advance. The semibarbarous Ch'in dynasty (221-206 BC) first established the centralized imperial system

that was to govern China during stable periods. The Great Wall was begun in this period. The native Han dynasty period (202 BC-AD 220), traditionally deemed China's imperial

age, is notable for long peaceable rule, expansionist policies, and great artistic achievement.

The Three Kingdoms period (AD 220-65) opened four centuries of warfare among petty states

and of invasions of the north by the barbarian Hsiung-nu (Huns). In this inauspicious time China experienced rapid cultural

development. Buddhism, which had earlier entered from India, and Taoism, a native cult, grew and seriously endangered Confucianism.

Indian advances in medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and architecture were adopted. Art, particularly figure painting and

decoration of Buddhist grottoes, flourished. Feudalism partly revived under the Tsin dynasty (265-420) with the decay of central authority.

Under the Sui (581-618) and the T'ang (618-907) a vast domain, much of which had first been assimilated to

Chinese culture in the preceding period, was unified. The civil service examination system based on the Chinese classics and

a renaissance of Confucianism were important developments of this brilliant era. Its fresh and vigorous poetry is especially

noted. The end of the T'ang was marked by a withdrawal from conquered border regions to the center of Chinese culture.

The period of the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms (907-60), which was a time of chaotic social change, was followed by

the Sung dynasty (960-1279), a time of scholarly studies and artistic progress,

marked by authentication of the Confucian literary canon and the improvement of printing techniques through the invention

of movable type. The poetry of the Sung period was derivative, but a new popular literary form, the novel, appeared at that

time. Neo-Confucianism developed systematically. Gunpowder was first used for military purposes in this period.

While the Sung ruled central China, barbarians—the Khitai, the Jurchen, and the Tangut—created northern empires

that were swept away by the Mongols under Jenghiz Khan . His grandson Kublai Khan , founder of the YŁan dynasty (1271-1368), retained Chinese institutions. The great realm

of Kublai was described in all its richness by one of the most celebrated of all travelers, Marco Polo . Improved roads and canals were the dynasty's main contributions to

China.

The Ming dynasty (1368-1644) set out to restore Chinese culture by a study of

Sung life. Its initial territorial expansion was largely lost by the early 15th cent. European trade and European infiltration

began with Portuguese settlement of Macao in 1557 but immediately ran into official Chinese antiforeign policy.

Meanwhile the Manchu peoples advanced steadily south in the 16th and the 17th cent. and ended

with complete conquest of China by 1644 and with establishment of the Ch'ing (Manchu) dynasty (1644-1912). Under emperors K'ang-hsi (reigned 1662-1722)

and Ch'ien-lung (reigned 1735-96), China was perhaps at its greatest territorial extent.

click here for website to Chinese civilization

|

|

|

Enter content here

CHINESE WRITING SYSTEM

Section: The Chinese Writing System Related: Language

The Chinese writing system developed more than 4,000 years ago; the oldest

extant examples of written Chinese are from the 14th or 15th cent. BC, when the Shang dynasty flourished. Chinese writing

consists of an individual character or ideogram for every syllable, each character representing a word or idea rather than

a sound; thus, problems caused by homonyms in spoken Chinese are not a difficulty in written Chinese. The written language

is a unifying factor culturally, for although the spoken languages and dialects may not be mutually comprehensible in many

instances, the written form is universal. The characters are written in columns that are read from

top to bottom and from right to left, or in horizontal lines that read from left to right. The Chinese characters, although

universal to all dialects, have proved to be an obstacle to mass literacy, for one needs to know at least several thousand

characters to read a newspaper and even more to read literary works. In an attempt to deal with this problem, the People's

Republic of China in 1956 introduced simplifications of commonly used characters. This was intended as a transitional phase

until a workable alphabet could be devised and adopted.

CHINESE ARTS

| |

| works of art produced in the vast geographical region

of China. It the oldest art in the world and has its origins in remote antiquity. (For the history of Chinese civilization,

see China.) |

1 |

| |

| Early Periods |

| Neolithic cultures produced many artifacts such as

painted pottery, bone tools and ornaments, and jade carvings of a sophisticated design. Excavations at B’ei-li-kang

near Luo-yang date materials found at that site to 6000–5000 B.C. An excavation in the early 1970s of the royal tomb

of Shih-huang Ti revealed an array of funerary terra-cotta images. In Henan, the village of Yang-shao gave its name to a culture

that flourished from 5000 to 3000 B.C. Ban-p’o pottery wares were handmade and the area produced a polished red ware

that was painted in black with designs of swirling spirals and geometric designs, sometimes with human faces. Later, at Ma-jia-yao

in Gansu, brush-painted pottery became more sophisticated in the handling of the design. Knowledge of ancient Chinese art

is limited largely to works in pottery, bronze, bone, and jade. |

2 |

| |

| The Early Dynasties: Ritual Bronzes |

| During the Shang dynasty (c.1750–1045 B.C.),

some of China’s most extraordinary art was created—its ritual bronzes. Cast in molds, these sacrificial vessels

display stylistic developments that began with early bronzes at Erh-li-tou and reached their apex at Anyang, the Shang capital city, where excavations in have yielded

numerous ritual bronze vessels that indicate a highly advanced culture in the Shang dynasty in the 2d millennium. The art of bronze casting

of this period is of such high quality that it suggests a long period of prior experimentation. |

3 |

| The ritual bronzes represent the clearest extant record

of stylistic development in the Shang, Chou, and Early Han dynasties. The adornment of the bronzes varies from the

most meager incision to the most ornate plastic embellishment and from the most severely abstract to some naturalistic representations.

The Later Han dynasty marks the end of the development of this art, although highly decorated bronze continued to be produced,

often with masterly treatment of metal and stone inlays. |

4 |

| |

| Buddhist Art |

| The advent of Buddhism (1st cent. A.D.) introduced

art of a different character. Works of sculpture, painting, and architecture of a more distinctly religious nature were created.

With Buddhism, the representation of the Buddha and of the bodhisattvas and attendant figures became the great theme of sculpture.

The forms of these figures came to China from India by way of central Asia, but in the 6th cent. A.D. the Chinese artists

succeeded in developing a national style in sculpture. This style reached its greatest distinction early in the T’ang dynasty. Figures, beautiful in proportion and graceful

in gesture, show great precision and clarity in the rendering of form, with a predominance of linear rhythms. |

5 |

| Gradually the restraint of the 7th cent. gave way to

more dramatic work. Major sites of Buddhist art in cave temples include Donghuang, Lung-men, Yun-kang, Mai-chi-shan, and Ping-ling-ssu.

For about 600 years Buddhist sculpture continued to flourish; then in the Ming dynasty sculpture ceased to develop in style. After this

time miniature sculpture in jade, ivory, and glass, of exquisite craftsmanship but lacking vitality of inspiration, was produced

in China (and was also made in Japan). |

6 |

| |

| Chinese Painting since the Fifth Century |

| Little painting remains from the early periods except

for that on ceramics and lacquer and tiles, and tomb decorations in Manchuria and N Korea.

It is only from the 5th cent. A.D. that a clear historical development can be traced. Near Dunhuang more than a hundred caves (called the Caves of a Thousand

Buddhas) contain Buddhist wall paintings and scrolls dating mainly from the late 5th to the 8th cent. They show first, simple

hieratic forms of Buddha and of the bodhisattvas and later, crowded scenes of paradise. The elegant decorative motifs and

certain figural elements reveal a Western influence. |

7 |

| A highly organized system of representing objects in

space was evolved, quite different from Western post-Renaissance perspective. Rendering of natural effects of light and shade

is almost wholly absent in this art, the greatest strength of which is its incomparable mastery of line and silhouette. One

of the earliest artists about whom anything is known is the 4th-century master Ku K’ai-chih, who is said to have excelled in portraiture. |

8 |

| The art of figure painting reached a peak of excellence

in the T’ang dynasty (618–906). Historical subjects and scenes of courtly life were popular, and the human figure

was portrayed with a robustness and monumentality unequaled in Chinese painting. Animal subjects were also frequently represented.

The 8th-century artist Han Kan is famous for his painting of horses. The T’ang dynasty also saw the rise of the great

art of Chinese landscape painting. Lofty and craggy peaks were depicted, with streams, rocks, and trees carefully detailed

in brilliant mineral pigments of green and blue. These paintings were usually executed as brush drawings with color washes.

Little if anything remains of the work of such famous masters as Yen Li-pen, Wu Tao-tzu, Wang Wei, and Tung Yuan of the Five Dynasties. |

9 |

| In the Sung dynasty (960–1279) landscape painting reached its

greatest expression. A vast yet orderly scheme of nature was conceived, reflecting contemporary Taoist and Confucian views.

Sharply diminished in scale, the human figure did not intrude upon the magnitude of nature. The technique of ink monochrome

was developed with great skill; with the utmost economy of pictorial means, suggestion of mood, misty atmosphere, depth, and

distance were created. During the Sung dynasty the monumental detail began to emerge. A single bamboo shoot, flower, or bird

provided the subject for a painting. Among those who excelled in flower painting was the Emperor Hui-tsung, who founded the

imperial academy. Hundreds of painters contributed to its glory, including Li T’ang, Hsia Kuei, and Ma YŁan. Members of the Ch’an (Zen) sect of Buddhism executed

paintings, often sparked by an intuitive vision. With rapid brushstrokes and ink splashes, they created works of vigor and

spontaneity. |

10 |

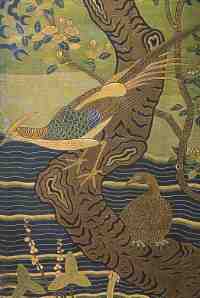

| With the ascendance of the YŁan dynasty (1260–1368) painting reached a new level

of achievement, and under Mongol rule many aspects cultivated in Sung art were brought to culmination. The human figure assumed

greater importance, and landscape painting acquired a new vitality. The surface of the paintings, especially the style and

variety of brushstrokes, became important. Still-life compositions came into greater prominence, especially bamboo painting.

During this time, much painting was produced by the literati, gentlemen scholars who painted for their own enjoyment and self-improvement. |

11 |

| Under some of the emperors of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) a revival of learning and of

older artistic traditions was encouraged and connoisseurship was developed. We are indebted to the Ming art collectors for

the preservation of many paintings that have survived into our times. Bird and flower pictures exhibited the superb decorative

qualities so familiar to the West. Shen Chou, Tai Chin, Wen Cheng-ming, T’ang Yin, and Tung Ch’i-ch’ang are but a few of the many great masters of this period. |

QUESTIONS ON CHINESE CIVILIZATION

1. What are some paleolithic discoveries found in China?

2. Why is Chinese civilization comparable to the Mesopotamian civilization?

3. Who is the founder the Chinese civilization? How did he achieve to unite the land?

4. What are the characteristic of the chinese writing system?

5. How did Buddhism affect Chinese culture? What are some buddhist practices still common among the Chinese?

6. What are some contributions made by the Chinese to science?

7. What are some medical practices contributed by the Chinese to modern medicine?

8. What are the characteristics of the Chinese garden?

9. What is your opinion of the Chinese people? Explain.

10. How did the Western civilization influence the Chinese culture?

11. Why are bamboos important in the life of the Chinese people?

12. What is the contribution of the Chinese to the world economy, aviation, medicine, warfare and space program?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bamboo Culture

Bamboo is one of the four favorite plants along

with Chinese plum, orchid and chrysanthemum, the so-called Four Men of Honor (Si4 Jun1 Zi3) by the Chinese. The characters

of the four plants are highly admired by the Chinese people so they want to be just like the four plants. In turn, the plants

have possessed some human nature. This is an example of the harmony between nature and human being (Tian1 Ren2 He2 Yi1).

You can find bamboo just about everywhere in China as long as it can

be grown. Gardens are usually good places to see bamboo, such as the famous Purple Bamboo Garden in Beijing and Guyi Garden

in Shanghai. The Bamboo Sea Scenic Area in Sichuan Province has become a popular destination, which consists of 28 peaks fully

covered with bamboo, thanks to the movie 'Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon.'

Bamboo culture is deeply rooted in the daily life of the Chinese.

Bamboo chopsticks are still the most common tableware in China.

Dizi (Chinese flute) is made of bamboo. People are still using paintbrush made from bamboo today. It is quite common to see

lucky bamboo and wenzhu (asparagus fern) in Chinese homes.

Bamboo Culture Festival has become popular in recent years.

There are many such festivals held in different places across China each year. To take part in a bamboo culture festival is

probably the best opportunity to learn the bamboo culture. During a bamboo culture festival, there are usually exhibitions

of bamboo carvings, poems and paintings. Bamboo painting is an important part of Chinese traditional painting. You can also

see all kinds of bamboos, listen to them as well as feel their spirit with your heart to bring you peace and harmony.

CHINESE INVENTIONS:

1. The Horse Collar: China. Third Century BC. About the fourth century

BC the Chinese devised a harness with a breast strap known as the trace harness, modified approximately one hundred later

into the collar harness. Unlike the throat-and-girth harness used in the West, which choked a horse and reduced its efficiency

(it took two horses to haul a half a ton), the collar harness allowed a single horse to haul a ton and a half. The trace harness

arrived in Europe in the sixth century and made its way across Europe by the eighth century.

2. The Wheelbarrow: China, First Century BC. Wheelbarrows did not

exist in Europe before the eleventh or twelfth century (the earliest known Western depiction is in a window at Chartres Cathedral,

dated around 1220 AD). Descriptions of the wheelbarrow in China refer to first century BC, and the oldest surviving picture,

a frieze relief from a tomb-shrine in Szechuan province, dates from about 118 AD.

3. The Moldboard Plow: China, Third Centrury BC. Called kuan,

these ploughshares were made of malleable cast iron. They had an advanced design, with a central ridge ending in a sharp point

to cut the soil and wings which sloped gently up towards the center to throw the soil off the plow and reduce friction. When

brought to Holland in the 17th Century, these plows began the Agricultural Revolution.

4. Paper Money: China, Ninth Century AD. Its original name was 'flying

money' because it was so light it could blow out of one's hand. As 'exchange certificates' used by merchants, paper money

was quickly adopted by the government for forwarding tax payments. Real paper money, used as a medium of exchange and backed

by deposited cash (a Chinese term for metal coins), apparently came into use in the tenth century. The first Western money

was issued in Sweden in 1661. America followed in 1690, France in 1720, England in 1797, and Germany not until 1806.

5. Cast Iron: China, Forth Century BC. By having good refractory clays

for the construction of blast furnace walls, and the discovery of how to reduce the temperature at which iron melts by using

phosphorus, the Chinese were able cast iron into ornamental and functional shapes. Coal, used as a fuel, was placed around

elongated crucibles containing iron ore. This expertise allowed the production of pots and pans with thin walls. With the

development of annealing in the third century, ploughshares, longer swords, and even buildings were eventually made of iron.

In the West, blast furnaces are known to have existed in Scandinavia by the late eighth century AD, but cast iron was not

widely available in Europe before 1380.

6. The Helicopter Rotor and the Propeller: China, Forth Century AD.

By fourth century AD a common toy in China was the helicopter top, called the 'bamboo dragonfly'. The top was an axis with

a cord wound round it, and with blades sticking out from the axis and set at an angle. One pulled the cord, and the top went

climbing in the air. Sir George Cayley, the father of modern aeronautics, studied the Chinese helicopter top in 1809. The

helicopter top in China led to nothing but amusement and pleasure, but fourteen hundred years later it was to be one of the

key elements in the birth of modern aeronautics in the West.

7. The Decimal System: China, Fourteenth Century BC. An example of

how the Chinese used the decimal system may be seen in an inscription from the thirteenth century BC, in which '547 days'

is written 'Five hundred plus four decades plus seven of days'. The Chinese wrote with characters instead of an alphabet.

When writing with a Western alphabet of more than nine letters, there is a temptation to go on with words like eleven. With

Chinese characters, ten is ten-blank and eleven is ten-one (zero was left as a blank space: 405 is 'four blank five'), This

was much easier than inventing a new character for each number (imagine having to memorize an enormous number of characters

just to read the date!). Having a decimal system from the beginning was a big advantage in making mathematical advances. The

first evidence of decimals in Europe is in a Spanish manuscript of 976 AD.

8. The Seismograph: China, Second Century AD. China has always been

plagued with earthquakes and the government wanted to know where the economy would be interrupted. A seismograph was developed

by the brilliant scientist, mathematician, and inventor Chang Heng (whose works also show he envisaged the earth as a sphere

with nine continents and introduced the crisscrossing grid of latitude and longitude). His invention was noted in court records

of the later Han Dynasty in 132 AD (the fascinating description is too long to reproduce here. It can be found on pgs. 162-166

of Temple's book). Modern seismographs only began development in 1848.

9. Matches: China, Sixth Century AD. The first version of the match

was invented in 577 AD by impoverished court ladies during a military siege. Hard pressed for tinder during the siege, they

could otherwise not start fires for cooking, heating, etc. The matches consisted of little sticks of pinewood impregnated

with sulfur. There is no evidence of matches in Europe before 1530.

10. Circulation of the Blood: China, Second Century BC. Most people

believe blood circulation was discovered by William Harvey in 1628, but there are other recorded notations dating back to

the writings of an Arab of Damascus, al-Nafis (died 1288). However, circulation appears discussed in full and complex form

in The Yellow Emperor's Manual of Corporeal Medicine in China by the second century BC.

11. Paper: China, Second Century BC. Papyrus, the inner bark of the

papyrus plant, is not true paper. Paper is a sheet of sediment which results from the settling of a layer of disintegrated

fibers from a watery solution onto a flat mold. Once the water is drained away, the deposited layer is removed and dried.

The oldest surviving piece of paper in the world is made of hemp fibers, discovered in 1957 in a tomb near Xian, China, and

dates from between the years 140 and 87 BC. The oldest paper with writing on it, also from China, is dated to 110 AD and contains

about two dozen characters. Paper reached India in the seventh century and West Asia in the eighth. The Arabs sold paper to

Europeans until manufacture in the West in the twelfth century.

12. Brandy and Whiskey: China, Seventh Century AD. The tribal people

of Central Asia discovered 'frozen- out wine' in their frigid climate in the third century AD. In wine that had frozen was

a remaining liquid (pure alcohol). Freezing became a test for alcohol content. Distilled wine was known in China by the seventh

century. The distillation of alcohol in the West was discovered in Italy in the twelfth century.

13. The Kite: China, Fifth/Fourth Century BC. Two kitemakers, Kungshu

P'an who made kites shaped like birds which could fly for up to three days, and Mo Ti (who is said to have spent three years

building a special kite) were famous in Chinese traditional stories from as early as the fifth century BC. Kites were used

in wartime as early as 1232 when kites with messages were flown over Mongol lines by the Chinese. The strings were cut and

the kites landed among the Chinese prisoners, inciting them to revolt and escape. Kites fitted with hooks and bait were used

for fishing, and kites were fitted with strings and whistles to make musical sounds while flying. The kite was first mentioned

in Europe in a popular book of marvels and tricks in 1589.

14. The rocket and multistaged rockets: China, Eleventh and Twelfth

Centuries AD. Around 1150 it crossed someone's mind to attach a comet-like fireworks to a four foot bamboo stick with an arrowhead

and a balancing weight behind the feathers. To make the rockets multi-staged, a secondary set of rockets was attached to the

shaft, their fuses lighted as the first rockets burned out. Rockets are first mentioned in the West in connection with a battle

in Italy in 1380, arriving in the wake of Marco Polo.

|

|

|

|